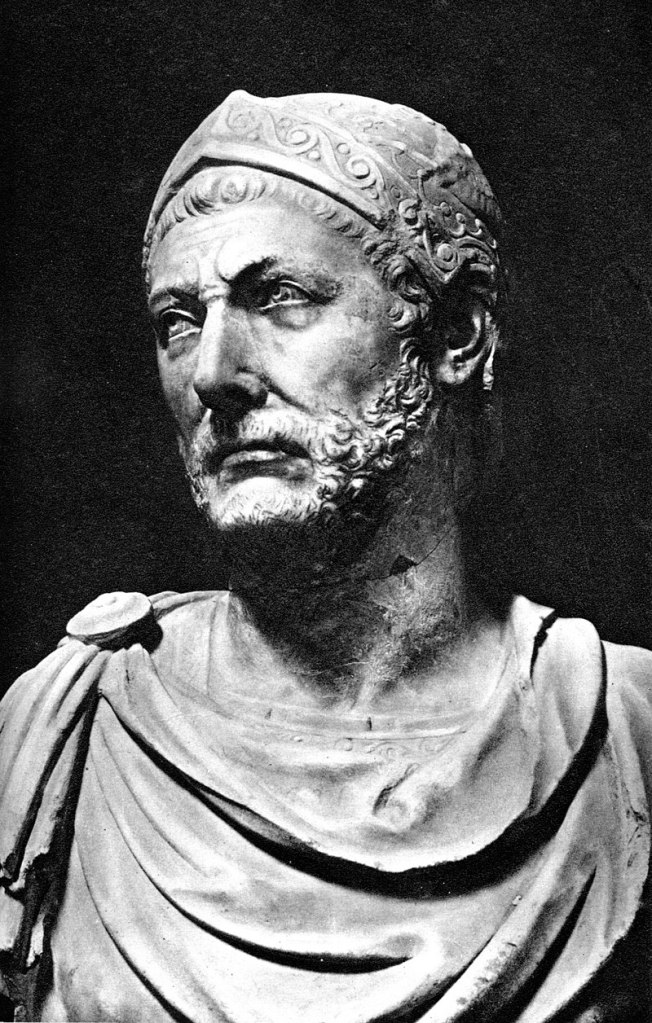

In 218 BCE, war broke out again between Rome and Carthage. This time, Carthage’s armies were led by Hannibal Barca, Hamilcar’s son. Hannibal was an absolute genius at battlefield tactics. Time and time again, he would defeat the armies Rome fielded against him.

After Hamilcar’s death, Hannibal was elected as his successor in leading Carthage’s forces in Iberia. He soon set to work on building upon his father’s conquests, defeating large armies of the local tribes and expanding Carthage’s territory and influence. This resurgence in Carthaginian power did not escape Rome’s notice. Wanting to create a presence in Iberia, they accepted the allied city of Saguntum as a Roman Protectorate. Hannibal viewed this as a violation of a previous treaty, which divided the peninsula between the two powers. Hannibal soon besieged Saguntum in retaliation. After an eight-month siege, the city fell. All inhabitants were either killed or sold into slavery. Rome was outraged by this attack, claiming that Saguntum was within their sphere of influence as outlined by the treaty. They demanded that Carthage hand over Hannibal to face justice. The Carthaginian government refused. The Second Punic War began.

Hannibal led an army of African and Spanish soldiers, but the best known part of his army was doubtlessly his contingent of elephants. He only had about 38 elephants in his army, but their mere presence terrified his enemies. A Roman soldier had probably never seen an elephant before, so being confronted with such an enormous armored beast must have been a truly frightening sight. It would be like if we saw a Tyrannosaurus rex on the battlefield today. Despite their psychological impact, they were a liability to Hannibal’s army as well. Transporting elephants with an army proved to be a logistical nightmare, especially with the crossing that was soon to come.

Hannibal led his army out of Iberia, leaving his brother Hasdrubal in charge of the Carthaginian holdings in the peninsula. He traveled across Gaul, and entered Italy from the north. This meant taking his huge army through the Alps. He accomplished this journey in only fifteen days, but lost a large portion of his army, including many of his elephants, in the process. When he reached the other side of the Alps, he reinforced his army with warriors from the local Gallic tribes.

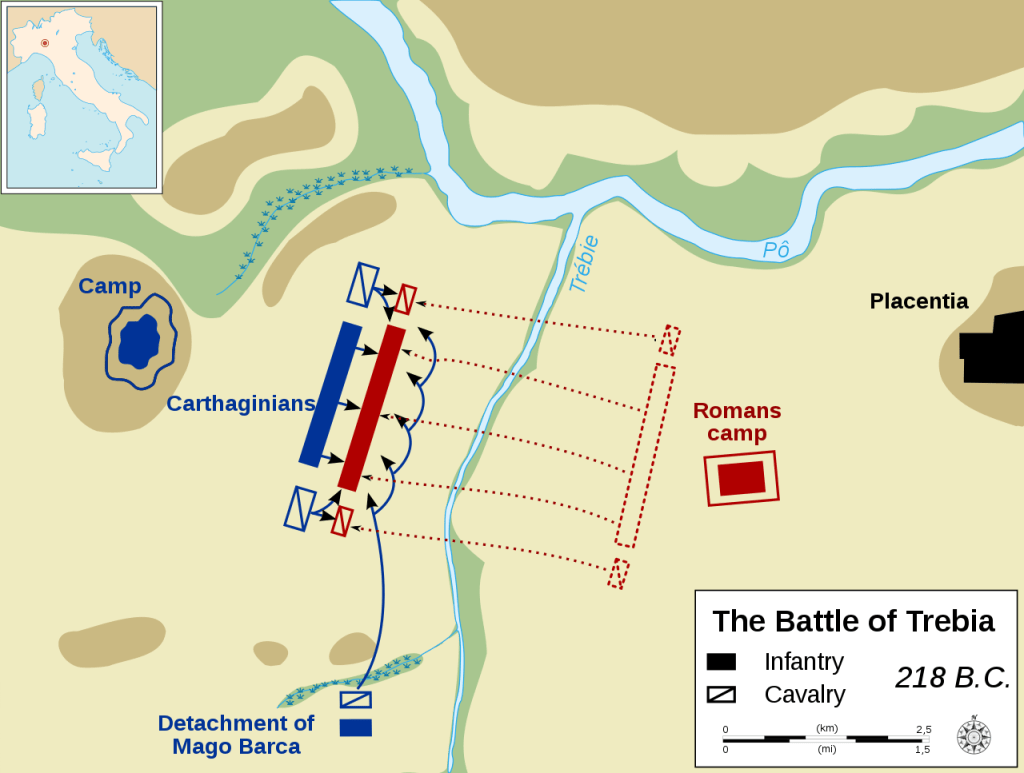

The first major engagement of the war was the Battle of the Trebia. Both of Rome’s Consuls combined their armies into a force of roughly 40,000 men and camped on the side of the Trebia River, across from Hannibal’s army. One of the Consuls, Publius Cornelius Scipio, was wounded from an earlier skirmish with Hannibal’s forces. He only avoided death because he was saved by his sixteen-year-old son, who shared his father’s name. As a result of Scipio’s wounds, overall command was given to the other Consul, Tiberius Sempronius Longus.

During the night before the battle began, Hannibal took 2,000 of his men, half infantry and half cavalry, and hid them in the long grass on his side of the river. They were placed under the command of Mago, Hannibal’s youngest brother. When the morning came, the rest of Carthage’s cavalry charged across the shallow water and launched a hit-and-run attack on the Romans. By the time the Romans could organize a defense, the horsemen were already in swift retreat across the river. The Romans quickly pursued. The Roman cavalry chased their Carthaginian counterparts but soon gave up and joined the rest of their countrymen. The Roman army marched across the river and faced off against the Carthaginian force. Hannibal placed his African troops on his right flank, and his Spanish troops on his left. He reserved the center for his new Gallic allies. The Romans took the opposite approach. The Roman troops were in the center while their allies took the flanks.

The two armies’ cavalry soon reengaged while the infantry lines advanced. The Roman troops soon met the Gauls and proved very effective. The Romans tore through the Gallic lines and forced them to give ground. At the same time, the Roman allies engaged the Carthaginian troops on the flanks. However, the Carthaginian cavalry had now chased off the Roman horsemen and they now returned. They crashed into both sides of the Roman allies and made them fight on two sides at once. It was then that Carthage’s hidden troops made their move. One thousand cavalry and one thousand infantry ran out of their hiding spots and attacked the Roman army from the back. The rear lines managed to hold their position, but the Roman army was now surrounded.

The Roman troops fighting the Gauls had now managed to cut through the last of their enemies, but could now see that the battle was lost. They promptly retreated, and managed to get to the nearby town of Placentia, all the while maintaining their battle formation. With their best troops out of the battle, the remaining Roman forces were quickly encircled by the Carthaginians. The Romans bravely made a last stand, but they were soon all picked off.

Roman losses were quite heavy, somewhere between 20 and 30,000 soldiers were killed. By contrast, Hannibal had only lost about 5,000 men. These losses were easily replaced, as news of his victory inspired many more Gauls to flock to his banner. The damage to Roman manpower was significant, but the damage to Roman prestige was much worse. The people of Rome were in a panic, and the Senate was scrambling to maintain order and deal with the crisis. Winter came soon, so there was a natural pause in the campaigning. Rome hurriedly raised a new army to deal with Hannibal when the spring came. This would just be the start of Rome’s misfortunes, however.

Links

Livy. From the Founding of the City, Book 21

The Second Punic War, World History Encyclopedia