After the defeat at the Battle of Lake Trasimene, the people of Rome war eager for revenge. The war was not going well. They had faced multiple defeats at the hands of Hannibal. The Romans were worried, and morale was low. They readied an army to strike back against Hannibal’s forces.

Rome mustered an army of eight legions, each consisting of 5,000 men. This force was joined by an equal number of allies, making an army of over 80,000 soldiers. It was commanded by both of Rome’s Consuls, Lucius Aemilius Paulus and Gaius Terentius Varro. The two Consuls had vastly different views on the best course of action. Aemilius favored Fabius’ strategy of avoiding direct confrontation, whereas Varro wanted a more aggressive policy. As they did not want to divide the army, they alternated command each day. This may not have been a bad idea if they had similar strategies in mind, but that was not the case. With so widely diverging commands, the army could not be used to its full potential. Hannibal’s army was smaller, about 50,000 men, but was commanded far more effectively.

The armies stood facing each other for two days. Hannibal made the most of this opportunity to observe the Romans. He studied every weakness he could see in the massive army and prepared his troops accordingly.

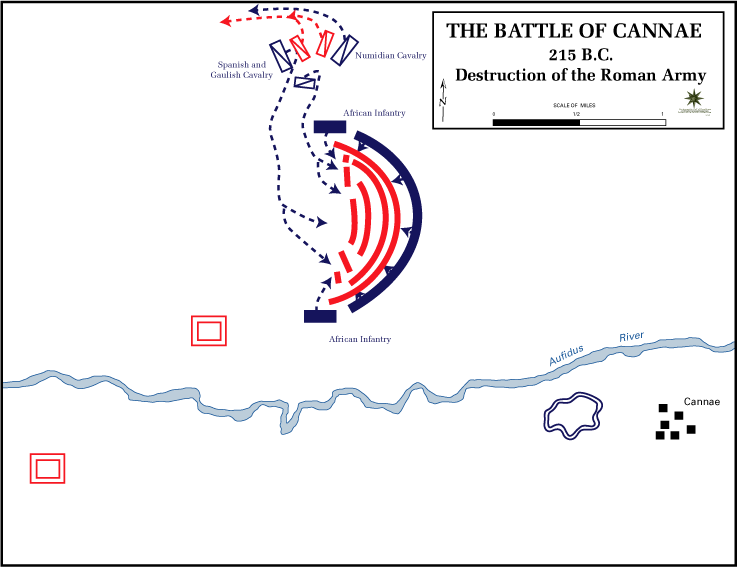

On August 2 216 BCE, the battle began. Varro massed his heavy infantry around the center of his army, hoping to overwhelm the Carthaginians by sheer weight of numbers. He had light infantry and cavalry on the flanks. Hannibal arranged his troops with a thinner center, his light infantry took the front lines and heavy infantry stood behind them and to the flanks. Hannibal himself took position in the center, right behind the front lines.

The Romans charged the Carthaginian lines, and the center began to give way. The Romans pushed their enemy back, gaining ground. Hannibal guided his men in a controlled withdrawal. As they retreated, the light Carthaginian infantry feel back to the sides of their heavier soldiers. As the Romans pushed forward, they were unaware of the Carthaginian army beginning to surround them.

Hannibal’s cavalry was far more numerous than Rome’s. They quickly drove off their Italian counterparts. Once they were clear, they charged the Roman army from the back. The Romans had heavy infantry to the front, light infantry to the sides, and cavalry to the rear. They were surrounded, and there was nowhere to run. Once the Carthaginians had completed their double envelopment, it was not so much a battle as a one-sided slaughter. The Romans, pressed in so tight, were utterly helpless against their foe.

The Romans were packed tightly together, and could not fight effectively. The smaller Carthaginian army cut down their enemies with ease. The exact number of Roman casualties is unknown. Polybius said 70,000 were killed, 10,000 were captured, and maybe 3,000 managed to escape. The later historian Livy gave 48,000 killed, 19,000 captured, and 14,000 escaped. Whatever the number of casualties was, it was catastrophic. Conversely, Hannibal only lost about 6,000 men, and they were mostly his Gallic allies, which were easily replaced.

Aemilius was among the dead, but Varro managed to escape. He returned to Rome, where the city was in a panic. Despite the huge loss of life, they commended him for not taking his own life, but choosing to fight on. He helped organize the appointment of Marcus Junius Pera as dictator, then returned to lead his army. Pera immediately levied the Roman people into a new army. He forgave debts and pardoned crimes of anyone who volunteered, and even allowed slaves to join. Rome soon had a large army ready for battle again.

Among the few Roman survivors was Publius Cornelius Scipio the Younger, who had earlier saved his father’s life at the Battle of the Trebia and had some successes against Carthaginian forces in Iberia. According to Livy, after regrouping in the town of Canusium Scipio foiled a plot by other survivors to desert Rome. Despite this disastrous defeat, he was still determined to win the war.

Despite his incredible victory, Hannibal did not receive greater support from the Carthaginian government as a result of his success. He could beat any army Rome sent against him in the field, but he did not have the necessary resources to take the city of Rome itself. No matter how brilliant of a general Hannibal was, there was a limit to what he could do without adequate support from his country. Hannibal sent his emissaries to the Roman Senate to negotiate a peace treaty. Even though the Romans had suffered a cataclysmic loss of life, they refused to even entertain the idea of negotiations.

What is perhaps equally impressive to Hannibal’s victory was the tremendous display of resolve shown by Rome in the aftermath. It is estimated that Rome lost between ten and twenty percent of its adult male population in one day at Cannae. This should have spelled doom for Rome. For comparison, Britain lost 6% of its adult male population in the entirety of World War I. Rome lost nearly three times that percentage in a single day. The mere fact that they carried on, let alone managed to win the war in the end, speaks volumes to the grit and fortitude of the Roman character. Most people would have given up. They didn’t. They resolved to learn from their defeat and emerge stronger. Today, Britain is rightly renowned for the courage and resolve it showed in two world wars, refusing to give up even when it stood alone against the Nazi war machine. Rome showed the same bravery and stood firm in its darkest hour over two thousand years earlier.

Fabius took charge again in the wake of this defeat. He put Rome on tract to recover. Like an ancient predecessor to Winston Churchill, he provided an example of fortitude in the face of the crisis, displaying a stiff upper lip for the Romans to follow. He decreed that all mourning rites must be held within the home, so public life would carry on as usual in the city. He also required that these private mourning rites be finished within one month. He allowed the people of Rome to grieve, but set their sights on recovery. Knowing that the war would not end anytime soon and would not be won easily, the people of Rome resigned themselves for the long, difficult task ahead.

Links

The Histories, Book III, Polybius.

Ab Urbe Condita, Book XXII, Livy

The Battle of Cannae, at the World History Encyclopedia